The Art Market: What the Numbers Say About American Ideals

In the summer of 2019, I took my Great Grandma Daisy to an art exhibit that was visiting the local Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. Admittedly, we had little idea of what to expect. We simply knew it was called 30 Americans and that it showcased Black art. As two proud African Americans, that was all the convincing needed. We were sold. Though upon stepping foot into what felt like a completely new museum, we experienced something that no advertisement could have conveyed. Immediately I was met with the vibrant colors and idiosyncratic strokes of Jean-Michel Basquiat in his 1982 piece, One Million Yen. To my left, one of Nick Cave’s iconic Soundsuits demanded my attention. Drawing influence from African art, his work blended commonplace materials into costumes that allow their wearers to transcend labels of race, gender, and identity. As we continued our ascent, we became haunted by the installation, Duck, Duck, Noose by Gary Simmons. Nothing could have prepared us to see a noose suspended from the ceiling, surrounded by a daunting circle of stools with the notorious hoods of the Ku Klux Klan perched on top. The mixed bag of emotions that each piece of art evoked in us reflected a story that captured what being African American means in its beautiful totality. We left exhausted. 30 Americans evoked something deeper than an appreciation for art—it was a deeply visceral experience that called on our spirits and spoke to our souls through the often-unheard voices of Black artists.

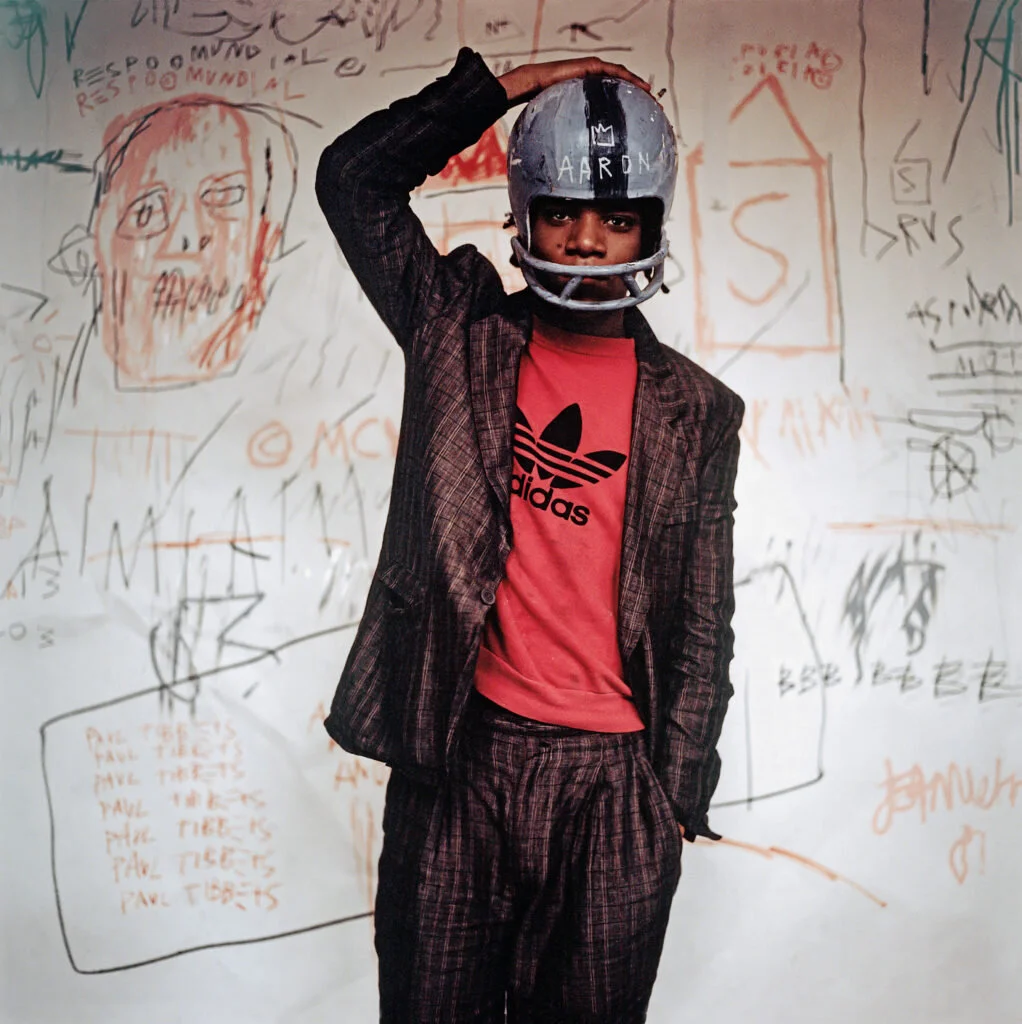

Throughout the years, there has been an undeniable growth in demand for Black art. One simply has to look at the price of a Jean-Michel Basquiat painting that sold at a 2017 Sotheby’s auction. At a healthy price of $110.5 million, Untitled became the most expensive American painting ever sold, topping Andy Warhol’s Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) which auctioned for $105.4 million. This, and other groundbreaking advancements in the marketability of Black art, has led many to agree with the sentiments of New York curator Todd Levin regarding the trajectory of the market. In a 2018 article from The New York Times, Levin stated that recent groundbreaking purchases have “signaled that finally African-American artists are regarded as having the same historical value and price points as their peers.” Though while it is certainly true that Black artists have experienced long-due progress in the reception of their work, Levin’s statement seems generous when one takes a closer look.

Photograph: 'Jean-Michel Basquiat Wearing an American Football Helmet' (1981) by Edo Bertoglio; Courtesy of Maripol; Artwork: © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, the estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat; licensed by Artestar, New York (Source: theatlantic.com)

The market for African American art is extremely top-heavy. When you take Jean-Michel Basquiat out of the picture, African American artists account for $460.8 million of the global auction market—a meager .26%. Basquiat’s rise to prominence as a cultural icon is inspiring to say the least. From fashion, to hip hop, to the walls of billionaires, it seems like the reach of his influence has no limit. Nonetheless, what his story does not tell is the plight that the majority of Black artists continue to face in a white-dominated market. This disparity runs deeper than whose work is being sold at a Sotheby’s auction. The Eurocentric art market manifests into the representation of Black art in museums and galleries across the nation. This is indicative of the fact that just 2.37% of all acquisitions and gifts at the 30 most prominent art museums are from African American artists. Simply put, museums do not buy Black art. And that is not owed to a lack of Black artists in the space, a number that has been steadily on the rise. Rather, it becomes clear that as the number of artists continues to grow, another figure must follow suit—the number of Black curators.

Curators serve as the backbone of the art industry. They determine the kind of work a gallery may buy, the pieces they display, and the ways in which they display them. As a result, for Black art to make its way into galleries, it must first be sought after by the curators who run them. This proves dismal when, as found in 2018 by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, only 16% of curators in the United States are people of color. That number becomes even smaller when only those who are Black are taken into account. It took a quick search on the internet to discover that, indeed, of the 12 curators at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, none of them were Black. It is no wonder that 30 Americans made the Nelson feel so refreshing. Underrepresentation of Black museum staff lends itself to an environment that lacks the necessary urgency to elevate the voices that have been shunned from the mainstream. It furthers a legacy that celebrates and caters to the upper echelons of society, only to further marginalize Blackness to the periphery of conversation. And while it is possible to start to shift this narrative under the status quo-- white curators have certainly curated Black art in the past-- it will take reimaging what museum leadership looks like to truly ungird this issue from its roots.

Left to right: Rashid Johnson, Nick Cave, Kalup Linzy, Jeff Sonhouse, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Barkley L. Hendricks, Hank Willis Thomas (front row), Xaviera Simmons, Purvis Young, John Bankston, Nina Chanel Abney, Henry Taylor, Mickalene Thomas (front row), Kerry James Marshall and Shinique Smith. Photo credit: Kwaku Alston, December 5, 2008 (Source: rubellmuseum.org)

For even when Black art is incorporated in galleries organized by white curators, other implications can start to arise. Artists for years have had to fight back against a phenomenon coined the “white gaze” because of such disparity. This scrutiny from the predominantly white market has historically pigeonholed Black artists into creating work that is deemed acceptable according to Eurocentric standards. In other words, Black artists too often must choose between expressing their sometimes-harrowing experiences and the marketability their livelihoods depend on in the art world—I can’t help but wonder if 30 Americans had not been curated by Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, an African American woman, would Duck, Duck, Noose have been shown? At the end of the day, it is impossible to be certain. However, one thing is: there is no such thing as American art without Black art. Therefore, until proprietors reexamine who they represent and how they go about doing it, the scope of America’s artistic past, showcased in galleries nationwide, will remain incomplete. And unfortunately, progress within the auction market will, too.

When I reflect on my first visit to 30 Americans, I am overcome with a sense of nostalgia. It feels comforting to bask in the memory of being surrounded by work I could see myself in. Work I could see Grandma Daisy and those who came before her in. Though the reality is, the market for Black art has a long way to come before it can achieve anything reminiscent of equity. Though I still have hope that by championing representation in all facets of the industry, curatorial staff especially, a more balanced landscape can be bred. I have hope that over time, Jean-Michel Basquiat can become a powerful example, not a token exception.