The Times, they are a'changin'

Americans have grown tired of watching commercials. Consumers’ frustration with commercials was first channeled into widespread adoption of recording devices like TiVo and DVRs, which made their way into seemingly every home in the U.S. But every year, on the first Sunday in February, perhaps paradoxically, millions of viewers turn on their TVs during the Super Bowl—sometimes, just to see the ads.

This year’s Super Bowl featured the usual slate of promoters, like mainstays Budweiser, Chevrolet, and Doritos. One commercial, though, came as a surprise to many: a minute-long television ad voiced by Tom Hanks for The Washington Post. Yes, the newspaper. It’s not the first time a newspaper has resorted to advertising itself, though, as The New York Times debuted a similar campaign during the 2017 Academy Awards, but for many viewers it was jarring nonetheless.

The ad did not aim to sell subscriptions. Instead, it focused on the value of journalism. Slogans such as “Knowing empowers us. Knowing helps us decide. Knowing keeps us free.” and then The Post’s trademark saying: “Democracy Dies in Darkness” appeared on the screen. With CBS charging up to $5.25 million for a thirty-second spot this year, many Super Bowl watchers likely wondered how The Post could even afford to air its message. The resurgence of legacy news organizations—press clubs which existed before the rise of internet news—reveals how.

Around the turn of the century, many newspapers began a protracted collapse. With the rise of the Internet, classified ads began to shift online to crowd-sourced pages like Craigslist, placing the once-lucrative paper ad industry on its last legs. Without ads, newspaper companies began to suffer financially. Many daily papers were faced with possible bankruptcy as the Great Recession hit in 2008 and 2009. Over the course of just three months in 2009, 33 daily papers were threatened as their publishers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. That list included the Journal Register Company, publishers of the New Haven Register; The Philadelphia Newspapers LLC, publishers of The Philadelphia Inquirer and the Philadelphia Daily News; the once-titanic Tribune Company, publishers of the Los Angeles Times and the Chicago Tribune; and the Star Tribune in Minneapolis.

No paper, no matter how large or influential, went truly unaffected. Cities and metropolitan areas with two major daily papers saw many of those publications close their doors or merge with regional papers. Even the nation’s three most widely circulated papers— The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post— felt the crunch.

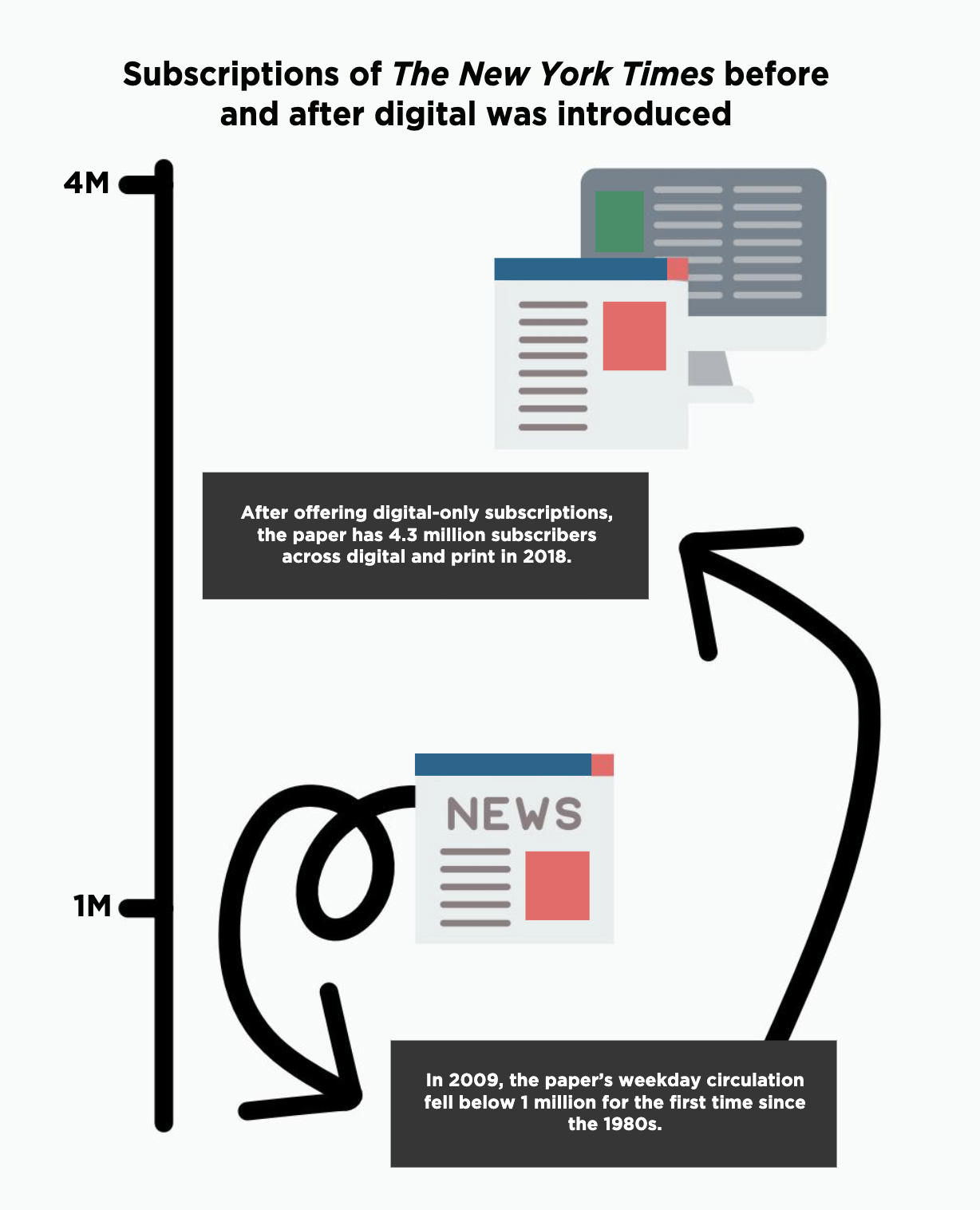

According to the Pew Research Center, the total revenue of U.S. newspapers as garnered from advertisements and circulation peaked at $49.2 billion in 2006. By 2012, that number had been cut in half to $25.8 billion. The New York Times reported similar numbers: a drop from $3.2 billion in 2006 to $1.5 billion in 2012. In 2009, the paper’s weekday circulation fell below 1 million for the first time since the 1980s. Print journalism was indisputably in a deep hole. But The Times and other large publications have since seen their numbers rebound. In 2017, The New York Times reported $1.7 billion in annual revenue, an 8% increase over the prior year.

So, how did The New York Times dig itself out from the hole threatening to consume the entire newspaper industry?

Cost-cutting began with physical changes a reader could feel when holding the paper in their hands. In 2007, The Times began to print on paper was that is 12 inches in width, rather than their original 13.5 inches. The Metropolitan section was merged with the main National & International News sections. Sports and Business also consolidated, save for on Saturdays and Sundays when sports gets its own insert. Cutting the page size saved the paper $12 million annually.

The New York Times succeeded in making money online as well. The Times set the standard for feature digital reporting in December of 2012 when it published “Snow Fall,” a six-part series covering the 2012 Tunnel Creek avalanche that occurred in the state of Washington. The story featured videos, photography, and interactive maps available online that allowed readers to experience the story more viscerally and completely than they could in newsprint.

“The story featured videos, photography, and interactive maps available online that allowed readers to experience the story more viscerally and completely than they could in newsprint.”

The Times, realizing the potential for success in this model, produced a whole section called The Upshot. While The Upshot undoubtedly delivers pertinent stories and worthwhile reads, its use of interactive maps is what makes it most notable. With this section, the Times aimed largely not for the eyes of its older readers, but instead those of Millennials and younger readers who understand and enjoy navigating technology.

However, they did not stop there. The Times now offers digital-only subscriptions for audiences that do not want or need a paper to land on their doorstep. Over 3.3 million individuals pay for these digital-only subscriptions, which produced $400 million in revenue in 2018. In the first quarter alone, 30% of the paper’s total new subscribers came from digital products like their daily crossword and cooking apps. In total, the paper has 4.3 million subscribers across digital and print—meaning that over ¾ of all readership is taking advantage of the online-only option.

“Retention of our core digital news product remains a very encouraging story,” said Mark Thompson, The New York Times Company’s chief executive, during an earnings call with investors in the spring of 2018. “We continue to retain the post-election cohorts, some of whom are now well over a year into their subscriptions at least, as well as earlier cohorts.”

The Times has also found success with trendy audio products like its podcasts. “The Daily,” a twenty minute piece pushed each weekday which covers topical news, has become a smash hit. Thompson, in expounding on the successes of the paper, has described podcasts as an excellent method for “getting Times journalism in front of new audiences and further[ing] the reputation of The New York Times.”

Big bucks still do exist in advertising, too. The New York Times saw digital advertising rise 8.6 percent in 2018. Digital advertising also surpassed print advertising for the first time in the fourth quarter, jumping 23 percent to $103 million. Over the last year, print ad revenue fell 10 percent to $88 million.

Armed with these positive numbers, Mr. Thompson has set one more lofty goal for the Times: “to grow our subscription business to more than 10 million subscriptions by 2025.” For now, America’s most iconic paper is just under half-way to that mark. So, expect to see more prime-time TV ads for newspapers sprinkled in with Bud Light and Burger King through Super Bowl LX.