A Remedy or a Curse: Will QE Help or Peril the World Economies?

Coronavirus has quickly dwarfed the Great Recession, making many national banks and governments resort to unconventional measures. Essentially, it has forced many states to "print more money," even driving emerging markets to jump on the trend. The monetary policy that names the tool, which allows central banks to introduce higher volumes of capital into the market, is called quantitative easing (QE). The implications of global QE asset purchases reaching $6 trillion and beyond may not yet impact the prices and stimulate the borrowing and the economic recovery in the short run. However, ignoring QE's downsides and its inflationary potential will inevitably negatively impact businesses in the future provided there are no other measures of assistance.

Quantitative Easing Overview

QE names the central bank’s decision to purchase long-term securities from the open market. In layman’s terms, the central bank buys equities and debts that hold some monetary value, so that the sellers can receive more money. As a result, the amount of money in the economy increases, helping to stimulate borrowing and selling. Because the central bank creates money out of thin air to complete the purchase, the monetary policy has also received the term "money printing." Correspondingly, the increased money supply makes it easier for banks to lend and borrowers to borrow, which spurs economic growth.

World Examples of QE and Outcomes

QE is not a new tool, and it has previously found its implementation in Great Britain, Sweden, and Japan, among many other countries. In 2016, QE in Great Britain was increased to help the economy after the EU referendum. While boosting the confidence of the businesses and stimulating borrowing, in the long run the policy still holds with rates close to zero, indicating that the policy has not worked empathetically. It made the QE a status quo instead of an emergency measure, increasing costs of imported goods, setting the scene for deflation, and increasing operating costs for businesses.

QE by year in the UK. Source: Bank of England

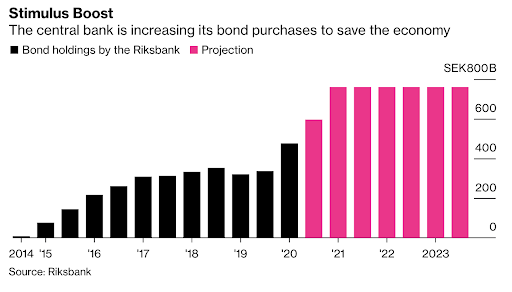

Earlier in 2015, Sweden has also implemented QE, making the monetary markets arguably more liquid, decreasing interest rates, yet increasing growth rates in mortgage loans and loans to Swedish non-financial corporations. Nevertheless, the available money in the economy has barely changed and the inflation target, tracked through the Consumer Price Index (CPI), was not achieved, and deflation was recorded in some months. Such a situation is dangerous since consumer spending and business output fall during deflation, making the latter cut down on production costs, reduce the workforce, which further impacts the unemployment, spendings, and economic output.

Finally, Japan's central bank has been implementing QE since 2001. The policy made Japan the most indebted country in the world. The enormous public debt scares away investors and harms overseas returns and domestic asset returns, concealing local interest rates. Since investors are bothered by the high risk and debt ratios, there are fewer funding opportunities for the local businesses, who already lose on the currency exchange, imported materials, and maintaining overseas departments.

The three countries took the policy implementation to different extents, yet in each, the interest rates plunged dramatically, making both Sweden and Japan pay money to the businesses for borrowing, which cannot be healthy for the budget in the long run. However, neither country has suffered enough to prove it economically insolvent, which suggests that the implementations were followed by additional measures that helped maintain states’ wealth.

Quantitative Easing Today

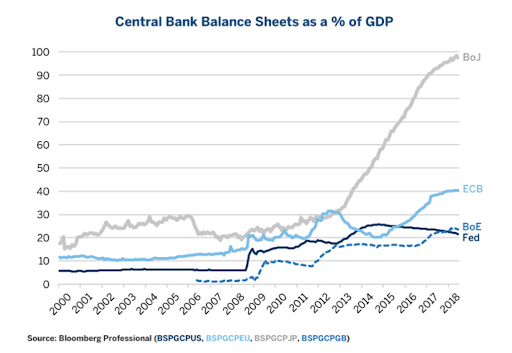

The graph shows Bank of England, European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve System, and Bank of Japan balance sheets with the latter having the highest total asset count resulting from a long history of QE implementation. Source: CME Group.

Unlike the examples described above, the QE examples implemented nowadays are far more common, more desperate, and bear more widespread effects as more nations implement it. The countries mentioned above have all resorted to quantitative easing once again, yet now their abilities to follow through the further QE maintenance have almost exhausted itself due to a prolonged policy implementation before. For the UK, the QE has risen by almost 100 billion pounds since March this year. Sweden has added another 200 billion kronor and prolonged the program until the June next year, while Japan carries on with its more than 30 years of QE maintenance to stick to its 2% inflation target.

An estimated $6 trillion in global QE asset purchases in 2020 is more than half the cumulative global QE total seen over nine years since 2009. The widespread interest cuts and monetary and fiscal policy implemented will influence the speed of the economic recovery; however, countries cannot overestimate the efficacy of the monetary tool and must keep in mind the long-term effects of it for businesses, as their confidence determines future economic development.

Currently, the global QE is rising with no inflation in sight. At the same time, unemployment keeps creeping upward and economies continue shrinking, signaling that the pandemic has a far more substantial impact than expected and indicating the insufficient support that the current fiscal and monetary policies provide. These will be felt hard by small and medium businesses that are currently protected by varying degrees of support from their state governments and are feeling most hit in the underdeveloped economies, where an aggregate $1.2 trillion in overall fiscal-support measures was provided compared to the $7.6 trillion in the developed states.

Sweden’s QE since 2014. Source: Bloomberg

While the developed economies will still recover from the shock that impacts their currencies, deflation, and unemployment due to numerous benefits and protection policies, emerging markets may find it harder to return to the previous growth rates. Businesses may feel more comfortable with lower interest rates, as the example of other countries described above shows, and it may further incentivize the growth return like Japan's case indicates. Nevertheless, deflation has been looming over the emerging markets for a while now, and the QE does not necessarily help the situation as Sweden's example has indicated. As a result, businesses will fear lower consumer spending and will cut down on production, committing to lowering profits.

Besides, investors may fear the loss of money due to changes in currency and interest rates and pull out their funds, further damaging the financial situation of businesses. Similar reaction was seen during the recent QE implementation by the Fed in March this year, after it decided to buy $107 billion worth of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. That same day, the Dow Jones lost 4.55% and the S&P 500 4.3%, marking their worst decline since the 2008 recession. Furthermore, as the UK's case demonstrates, higher inflation for imported goods due to changes in currency rates will drive up the operation cost, decreasing the money available to the businesses and their abilities to function overseas.

What Can Be Done To Maintain Positive Effects?

Hutchins Roundup has concluded that direct business assistance and employment protection are vital for consistent and long-term economic recovery. Since QE inserts liquidity to banks, the money may never leave them as they fear funding to the businesses whose balance sheet is hampered by the pandemic. New programs that lend to businesses directly are more effective than traditional QE measures since the money is directed towards the worst-hit sectors.

As for unemployment, the benefits for jobless citizens are primarily financed through taxes, which businesses pay, suggesting that the higher the unemployment, the higher taxes businesses may bear. More so, the businesses lose the incentive to hire more workers as less money is available to them. Hoping to save more money, they hold on to them, further impairing the recovery potential, leading to a liquidity trap, which enables the use of monetary policies as Japan's example has shown to us in the past.

Concluding Remarks

In essence, QE has a place as an emergency fix. However, it often becomes a status quo rather and forces central banks to carry on with it. The long-term duration of the monetary tool and varying supplementary measures can cause more uncertainty in the global economy, leaving businesses in emerging economies badly hit and decreasing their financial recovery potential. Consequently, business assistance needs to be provided directly rather than through the banks, protection of emerging markets needs to be counted in, and the long-term effects of the policy remain vital to consider.